Astronomers have achieved a groundbreaking milestone by directly observing two black holes orbiting each other in the distant quasar OJ287, located billions of light-years away.

These supermassive black holes complete an orbital cycle every 12 years, engaging in a cosmic dance that has fascinated scientists for decades.

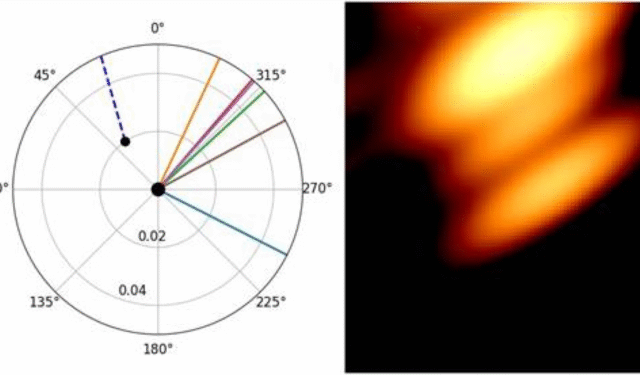

To capture this rare phenomenon, researchers from India’s ARIES (Nainital), TIFR (Mumbai), and global collaborators deployed a powerful network of telescopes. Specifically, they used NASA’s TESS satellite and the RadioAstron space telescope to obtain high-resolution radio images. As a result, the images revealed two distinct points of emission, confirming the presence of both black holes. Remarkably, the smaller black hole launched a jet of high-energy particles that twisted like a “wagging tail” as it orbited its massive companion.

Historically, scientists first noticed OJ287’s rhythmic flickering in 19th-century photographs. Eventually, by 1982, they began suspecting a binary system. Subsequently, Lankeswar Dey, under the guidance of Achamveedu Gopakumar and Mauri Valtonen, published the final orbital model in 2018 and 2021, solidifying the theory.

Then, in 2021, astronomers observed a sudden brightening—equal to the light of hundreds of galaxies—within just 12 hours. This dramatic event confirmed the second black hole’s activity. Furthermore, ground-based telescopes coordinated by Jagiellonian University in Poland validated the discovery.

Ultimately, this celestial choreography offers more than visual wonder. As the black holes spiral inward, they will eventually collide, releasing gravitational waves—ripples in spacetime that observatories like LIGO and Virgo have already detected. Therefore, OJ287 now serves as a natural laboratory for studying these cataclysmic events and deepening our understanding of the universe’s evolution.